Durga Chew-Bose of Too Much and Not the Mood

“What matters most on this planet for writer, Durga Chew-Bose, is spending time with art that makes her want to create art.”

Named as one of the Passerbuys Best Books of 2017, Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose has resonated with readers who have an attachment to the small and significant details of life that can only be described with her poetic writing. A collection of essays, the book takes its title from an entry of Virginia Woolf’s A Writer’s Diary in reference to Woolf’s frustrations with writing to please other people. Durga writes about the magic of the in-between moments that are often missed, how “an elbow propped on the edge of a table is an adverb.” One may find such an earnest relatability to the feelings that Durga writes of, as I did, be it about “women with implication” or “nook people,” a phrase that she and a friend coined to describe “those of us who seek corners and bays in order to redeploy our hearts and not break the mood.” The way she writes so lovingly about the women in her life led me to text my friend as we read the book together by exchanging short phrases and ideas, only to fall in love with the book more and more. Not only did Durga’s book stay with me, but with passersby, Alix Gutierrez and Nicole Steriovski, as well. So I hopped on the phone with Durga to know more about her writing process, favorite places in Montreal, and what art pieces and books that have been on her mind lately.

Jessica Jacolbe: Reading your book is one of the highlights of my 2017 actually. I read it during the summer, and my best friend and I would share passages of your book to each other that would spark very long text conversations. So, what led to your career as a writer? Is it something that you always wanted to pursue that led to the creation of Too Much and Not the Mood?

Durga Chew-Bose: I can’t remember if there was ever a moment of complete clarity when I dove headlong into becoming a writer. I was in college studying literature, and then after college I was trying to find places to publish some of my work. It wasn’t this grand plan, and even with the book. I hadn’t worked on a manuscript and then tried to find a place to publish it. It kind of worked backwards in that way. I published several essays online, and FSG (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) actually asked me if I’d be interested in collecting my essays somewhere.

In terms of what brought me towards writing, probably reading and watching movies, to be honest with you, is the easiest answer to this question. [Laughs] Watching movies makes me want to write. Sounds really simple, but I can’t think of anything that galvanizes me more. Then, reading and rereading. Those are the two things I do more than write. I think also feeling like a very visual person from a very young age, but not being a visual artist. For me, writing was kind of a way of communicating that.

JJ: Could you tell us about the process behind getting your book published or a step-by-step breakdown of how you put it together?

DCB: I was invited to do a reading. There was this series a while ago in Brooklyn called “Secret Admirer.” Someone curates a list of readers that would form their ideal reading, essentially, but you don’t know who the person is, hence the title “Secret Admirer.” I wrote a piece for it, and another one of the readers there was the writer, Luc Sante. From what I understand, he emailed Jonathan Galassi at FSG, and basically said, “Have you heard of this young writer? Here’s something she wrote, if you have time maybe you should meet her.” I went to his office at FSG and we just talked about books our first time. After that, he said, “Well, send me more of your stuff, and if you’d be interested in working on a book proposal or if you need help with that…” So I walked out of the office in a bit of a daze because I didn’t really know that’s what was gonna happen. I didn’t even tell anybody, kind of, when I sold the book. It wasn’t out of fear or it not necessarily being real. Writing is so much work and until you feel the benefits of the work, it almost feels like it’s not worth talking about. It was not the usual route, or what I feel might be the usual route, which is finding an agent, working on the book, and then placing it at a publishing house.

JJ: I remember reading one of the essays, Tan Lines, previously online, so how were you able to narrow down which essays you wanted to publish, or did you have to write additional essays?

DCB: Well, it’s 14 essays, and I think four or five of them were previously published. I tailored them more to the book, but also just basic internet vernacular, more blogging language that I maybe wanted to clean up. I definitely knew I wanted the majority of it to be original material. I worked with my editors, Emily Bell and Maya Binyam, about that. We talked a lot about the order of it. All of the previously published stuff is near the end of the book, too, or sandwiched between. For me, it felt like a good way to have this sort of crescendoing buildup to what a reader might be previously acquainted with, but then kind of have a coda of some new stuff to create the sensation of a wave.

I thought a lot about themes that were addressed in other essays, and what previously published stuff might anchor that or be in dialogue with the newer stuff. There was, of course, a lot of hesitation because one’s voice and interests change so much. I think sometimes when you work on a bigger project, stuff that’s even a little bit older, the sincerity in it or some of the observations might not pair well with the newer stuff. I think since a lot of my writing is rhythm-based too, it didn’t feel like too much discord, or just enough but not too much.

JJ: You write in the book about being a first-generation kid, and as a first-generation kid myself, I loved reading about your experience, especially in your essay D As In, and of course, Tan Lines. It felt so familiar to me in a way that I’m not used to seeing everywhere. What kind of reader do you write for, or how do you picture her whenever you’re writing?

DCB: With my book, I think it had a lot to do with not being around my friends when I was writing it. It was my way of staying in contact with them more psychically. The readers I had in mind were my closest friends or the people that I consider my writing confidants. I feel very, very lucky because some of the people I consider my closest friends in the world are also brilliant writers. Writing to them made me work harder and be as accurate as I can be, or to write to them, speak our secret language. In my mind, it was those women in my life.

I also think that, for instance, essays like “Tan Lines” or “D As In,” when I was writing them prior to the collection, I used to feel like there wasn’t really a place to be, for instance, first-generation but not just write about being first-generation. I wanted to write to a reader who similarly feels compelled by one’s heritage but not wanting to be boxed in by it. I always wanted to write about these ideas that are super relatable but so distinctly mine because I find there's nothing more connective than when you're so particular you're convinced no one will relate to what you're writing because you're describing something so categorical from your past. That specificity, it turns out, is what reaches the reader. I guess my ideal reader is someone who, like me, has tunnel vision, is interested in termite art, who zeroes in on things. Who builds images that feel, near in tone and effect, to pointillism. Like 'nook people,' which I write about.

“I find there’s nothing more connective than when you’re so particular you’re convinced no one will relate to what you’re writing because you’re describing something so categorical from your past. That specificity, it turns out, is what reaches the reader. I guess my ideal reader is someone who, like me, has tunnel vision, is interested in termite art, who zeroes in on things. Who builds images that feel, near in tone and effect, to pointillism. Like ‘nook people,’ which I write about.”

JJ: Yes! I loved reading about how you describe “nook people” because it did feel super relatable.

DCB: I tend to write to people who are, even when they’re at their happiest, there’s some kind of underpinning that might be a little bit pensive or sad. I’ve always related to that. Even if I’m writing about a moment that brings me complete joy in the book, I think I always have a tendency to not express that joy brightly. [Laughs] It’s like dimmed joy, and I think that that’s my reader who I was potentially writing to.

JJ: Coming from that, what’s your writing process like? What routine do you go through or what tools do you use, if any, to help you put it all together?

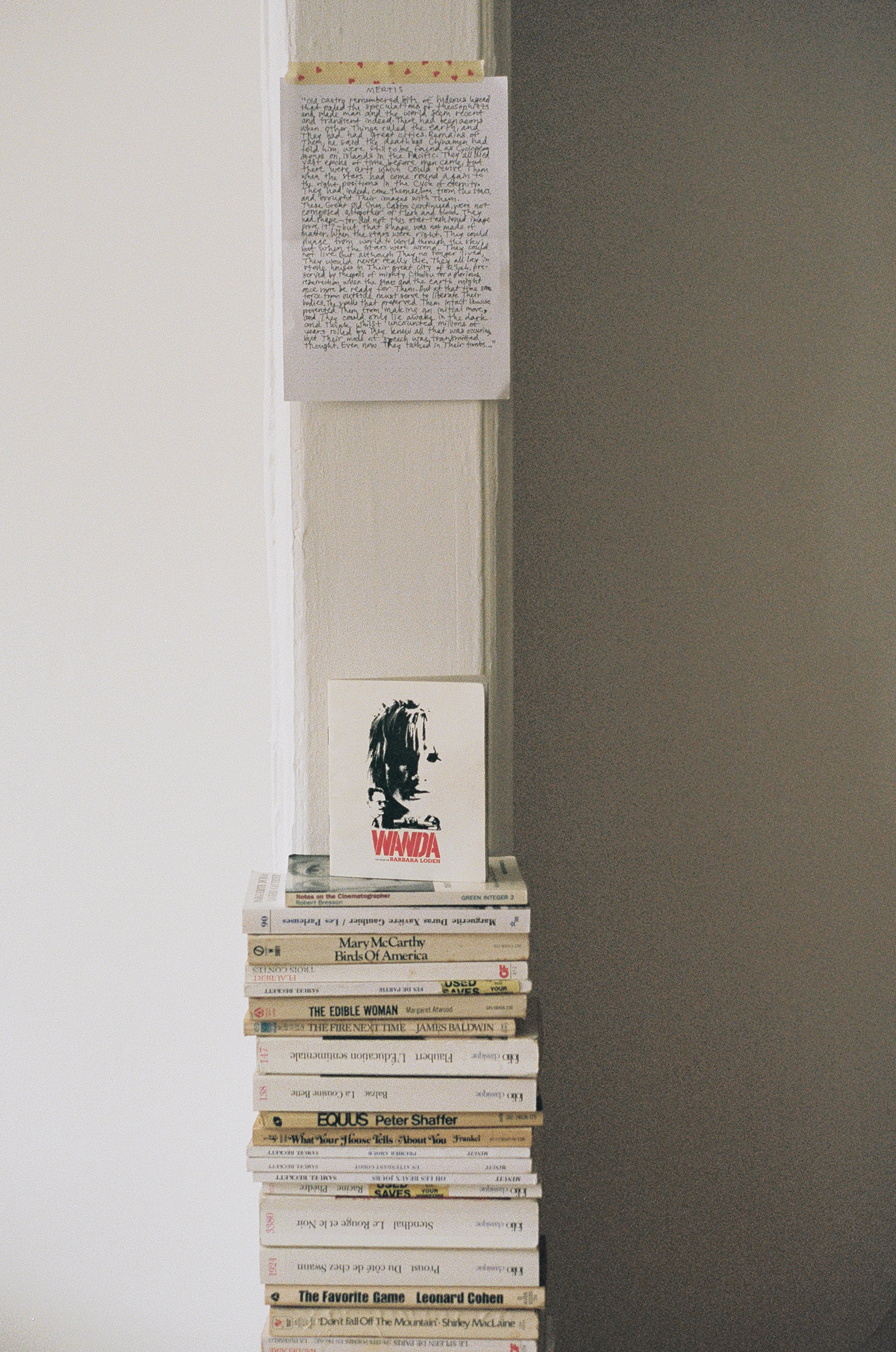

DCB: I guess a collection like this feels more like a tartan of who I am in some ways. I almost feel like there’s a physicality to it. I feel like I was living in a book fort while I was working on it. Keeping those books near that really have inspired me, rewatching those movies, like I said before, remind me why I’m so compulsive about certain topics that I need to write about. I finished most of the book in Montreal, living by myself in a new apartment, not knowing a lot of people. Even though I was born in Montreal, it was a return more than a decade later, so I didn’t really have an adulthood in this city. I wasn’t distracted by a social life, so it was very monastic.

I think one of the tools for me is self-imposed solitude. I feel like it can seem intense to some people, but I really don’t know any other way. I spent the month of November in 2015, entirely alone in Provincetown. Waking up super early, having a very plain breakfast, working until about 3:00 or something, and then I would walk to the ocean to see the sunset and its afterglow. Then walk back, cook dinner, and go to bed. It was distraction-free. That kind of stuff I find really helpful because there’s a lot of nonsense around writers, and I needed to cut out some of the noise. I don’t think I could have finished the book had I stayed in New York during that writing period. I try not to read anything brand new while I’m working. I try to return to whatever I’m familiar with. I feel like those stuff remind me of what it is I want to be doing, as opposed to comparing, which can be so dangerous.

I was writing a lot of letters with some of my friends, so I think that’s also helpful. Writing by hand, and just kind of sharing your every day to the people that you love was a good way to remain in contact with the friends who also are a huge part of why I write and who I write to. Keeping up that sense of correspondence, similar to what you were saying about your friend, of just exchanging passages. That sort of correspondence is really important to me because I feel so much of my writing is trying to connect ideas or images that I have no idea why they resurface in my mind, but there’s a reason. It’s my job, I feel, to kind of make that connection. Some people are very strict about their routines, and I’m quite comfortable procrastinating. In fact, I feel like nothing invigorates me more or magically makes the work happen, which is oxymoronic, I guess. Procrastination really does kind of provide fuel for me.

JJ: On the technical side, do you write usually by hand? I know you said with your letters you do, but for writing your book, what tools do you normally write with?

D.B.C.: I use Microsoft Word, but I also keep running notes in my phone of things that strike me when I don’t have a pen and paper. It could be as simple as a pair of words that says something sonic about them. I don’t know why that pair of words suddenly kind of parachuted down, but I need to document it. I have a running tab in my notes on my phone of words, images, turns of phrases, the way someone expressed shock or awe, people’s voices and how they string words together. I can find a quality to it, and I just need to keep it. I never know what I’m going to be doing with it necessarily, or if I’ll ever use it or it’ll merely be the title of something. I don’t write by hand, but I definitely have a lot of incomplete notebooks. [Laughs] The first 20 pages are full, then for whatever reason, I need to start a new notebook instead of completing the old one, I don’t really know why.

JJ: By living in Montreal and being away from New York, especially as a writer, do you have any recommendations about living in Montreal, or special places that you go to get away?

DCB: Montreal is a lot smaller than New York, so I feel like I don’t really have to go very far to seek out those quiet places. I live near a canal, and so I’ll go for walks along the canal a lot in the summer. Obviously in the winter, it’s been pretty brutal. It’s a real smooth wind down. It is nice to have that, and compared to New York, like probably every city, is more affordable. I work at SSENSE now. It’s a luxury e-commerce platform that has a magazine, and Joerg Koch is our editor-in-chief and I’m a senior editor there. I’m at the office all day, and then I’ll meet friends for dinner after. It feels less hectic than it did in New York.

I love Drawn & Quarterly Bookstore. It’s beautiful. It feels a bit like a clubhouse. There’s a paper store called Nota Bene that I really love going to. It’s on Avenue Du Parc. I love eating at this place called Larry’s. So delicious. I live in a neighborhood called Saint-Henri, and there’s a place called Satay Brothers. I just had dinner there last night. It was amazing. Then there’s also a place close to me called Le Vin Papillon, which translates to butterfly wine. It sounds ridiculous, but it’s funny.

I spent my entire twenties in New York, and that’s when you kind of find your spot and become a regular somewhere or feel like you have your regular routine. Now I’m in my early thirties, trying to figure out what makes sense for me. My family lives here too. My brother and his girlfriend had a kid last year, and that’s where I want to be spending most of my time, with my niece. I’m still trying to figure out what my life is like here, but that’s exciting too because I have to remain alert to liking something new or trying to find a new place.

JJ: One of my favorite parts about reading the book was underlining all the movies and books that you mentioned. I was like, “This is going on my list of everything I need to watch and read.” You touched on being a very visual person and being inspired by movies, so what is inspiring you currently and capturing your mind?

DCB: In terms of music, I feel like I’ve never been someone who’s really into music for whatever reason. Sometimes when I need to kickstart my writing there’s this one George Michael song I like, “Waiting For That Day.” My friend Marcelo got me into Caetano Veloso. I listen to him a lot when I’m writing. There’s one song by Sibylle Baier. She actually had a small part in Wim Wenders’ Alice in the Cities. There’s this song called “Forget About” that I listen to on repeat. I know some people can’t listen to music that have words when they’re writing, but if it’s the right song or if I’ve listened to it enough, it becomes wordless somehow. I always listen to this Ethiopian nun, Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou. It’s beautiful piano and totally mesmerizing, but what I really like is when you listen to an entire album it feels like certain songs might even be repeating a previous song’s refrain. I love Mamma Andersson’s and Peter Doig’s paintings. I tend to look at them a lot when I’m working. They just calm me, and I’m so familiar with them. They both paint winter in a very specific way that I feel is somehow part of the same family.

I just interviewed André Aciman. He wrote the novel, Call Me By Your Name. I’ve written an essay about the film, but speaking to him was really something because the book is incredible. It’s a really strange sensation to read a book after you’ve seen the movie, and I’ve seen the movie a few times. I find that movie really inspired me this year. I think also because sometimes I feel insecure about how much I write with feeling and about feelings. Sometimes in encountering a film or a book that is devoted to feelings, I feel less alone in that pursuit.

I’m reading Sheila Heti’s new book that’s coming out in May, Motherhood. I finished that, and I just immediately flipped it back open and started reading it, and it’s incredible. When I first read How Should a Person Be, it was a very specific time in New York for me. I had just met my best friend, and I was listening to Frank Ocean’s “Channel Orange.” Reading her again, she’s so particular and there’s nobody else like her. I feel like I’ve been sent back in time, but in the best way. Not regressive or anything. I feel warm about reading her, like that sensation when you catch up with an old friend and you fall right back into the same rhythms and it’s not odd or awkward at all. Her new book is incredible.

JJ: Do you have any recommendations or advice for writers, if there’s anything they can do to become a better writer or find their voice?

DCB: I guess that depends on what someone wants to write. Yesterday on my phone call with André Aciman, he said something about poetry that really struck me. He said that what’s wonderful about poetry is that it tells you things that you’ve already known. I think that’s why I’m so drawn to poetry because even if you’ve never read the poem, it can feel like a déjà vu. If a poem has its way with you, it can give you the sensation of just feeling previously acquainted with it, even if it’s brand new. It’s such a tension that I’m really drawn to, so I think reading poetry, for me as a writer, has always been really important. Brevity can funnel what’s important, right? I’m clearly not very good at brevity, so maybe I just like it to elixir and remind myself what’s up. I don’t know if I feel like I have the authority to say, “This’ll help you become a better writer!” Honestly, just reading. Read more than you write, and come up for air with the people that you love and listen to your parents’ stories and be open-hearted about how you listen and how you read and who you pay attention to and who you love. I think that is all really important to writing. I also think that really honoring the voice in your head and not letting in too much doubt before you can really honor that voice. It can seem really extreme, but write for yourself first. Somehow writing for the people that you love and love you back is like a version of writing for yourself, but don’t write to impress anyone. Don’t write to win anybody over.

I know not everyone agrees with me on this, but not all writing needs to argue a point. You don’t always have to be in search of the right idea. The writing could be just the search, at least in my case. I think that has always been some sort of guiding principle for me. I also think one of the reasons why I reread and rewatch certain films a lot is because if you have those pieces of art that do something to you, there’s a reason. It might not actually be linked to what you’re working on. When I say I’m looking at Peter Doig’s paintings, it’s not because I’m writing about Peter Doig. It’s not because I’m writing about the wilderness. In fact, if I were to think of an artist whom I love, whose work doesn’t really seem to pair with what I do, it might be him, but something about his work, I return to. That return, to me, is important, and that that exists is a reason for me to do the work that I’m doing. I can’t really put words to it. It’s just a feeling, but it’s there. It makes me want to create, and that’s the thing that matters to me most on the planet is encountering art that makes me want to make art.

Words by Jessica Joyce Jacolbe & Photography by Rebecca Storm