Meet Zari Gesce

Pharmacist Zari Gesce is likely to be found among a spontaneously formed group of other Iranian creatives, huddled around a hundreds-of-years-old text in the library (read on for her specific room recommendation), working on one of the many projects she has up in the air surrounding her desire to create an archive of what it means to be Iranian right now, in a moment she feels is precious and fleeting. We had the chance to talk to Zari about her work in addiction medicine and academic detailing, her ad hoc approach to connecting with her heritage, and how newfound community in NYC has given her the feeling of “home” for the first time in her life.

♫ Listen to zari’s playlist | ⌨ zari’s last google search

on her morning routine

The first thing I see when I open my eyes is my dog, and we take a moment to snuggle. On a perfect day, and the weather's been so nice, we take a walk first thing in the morning before I start my work day. I'm not that hungry in the morning, so maybe I’ll have some tea or Naan-o Paneer-o Sabzi, a classic Iranian breakfast of cheeses and herbs — recently, I’ve been eating it all the time with pita bread. Work starts at 9:30 AM for me because most of my team works in the Pacific time zone. It's nice to have some downtime to go through emails, before everybody else wakes up and logs in.

on emigrating to the us from iran

I moved to the States when I was 15 years old, in high school. My parents decided to emigrate, it wasn't a personal decision. I just embrace that as something that we had to do. It wasn’t necessarily politically motivated, but we moved because of the potential for a better future. My parents thought it would be better for us to grow up here, there’d be more opportunities for us, especially as girls. My dad was a lawyer, and my mom was a teacher, and just like any other immigration story, they sacrificed so much when we moved. We started from zero, my parents were working bare minimum-paying jobs that they still have to work at because they can't retire, and we moved around a lot. We moved to Massachusetts that first year, then we moved down to Texas, because Boston turned out to be really cold! My uncle used to live in Plymouth, Massachusetts, which is a really fun story. I like to tell people about us immigrating, to Plymouth like the Puritans. It was really significant in that we were following the first US immigrants’ footsteps. But we lasted only nine months. My parents had some friends down in Texas, I finished high school and went to college there.

““As pharmacists, we learn a lot about how to be better listeners and build empathy, for which I am grateful, because I can apply that in my personal life as well. The goal is to never go in to an interaction with a doctor and tell them ‘you’re not prescribing this correctly.’ You’re there as a resource, to help them brainstorm about what’s going on.””

on her academic path

I studied biology, I was pre-med. I really wanted to major in art, but my parents were like, “We sacrificed a lot for you, you're not gonna major in art.” It took me years to get over that. Now, I really appreciate it, because I like the job I have, as a pharmacist. I was able to find a niche within science that works for me and my personality, but to be honest, the search was brutal. I didn't really feel like I belonged with the other people who were pursuing the same major. I picked biology because there were a lot of pictures in the textbooks that were pretty to look at, and it turned out I was great at it. I can memorize things very easily — I’m very visual, so I memorize in a pictorial way. Not only did I graduate with a biology degree, but I got into pharmacy, which is a highly competitive program, and that was also because I didn't want to go to medical school or dental school. It was a process of elimination. I didn't want to touch people or see blood, so like nursing or medical school wasn't for me. Pharmacy work is perfect for an introverted person, you have your space, away from the crowds, but in pharmaceuticals in the States, you can pursue clinical fields, so as a pharmacist you can actually work in clinics to see patients and manage their medications.

We usually work as a team, with the doctors. A patient gets diagnosed, and then they are sent to us for medication management. There are a lot of fields that pharmacists are getting into — blood pressure issues, heart failure, other chronic conditions that require people to go through different medications to figure out the best treatment. Pharmacists are now offering that assistance, which is nice, because doctors are usually really busy, and we're the drug experts, so we know what the side effects of a medication could be and some of the different configurations of treatment that might work for different patients. I decided to do a residency in mental health and addiction medicine, so for two and a half years after I graduated from pharmacy school, I did clinical training.

““I would encourage people to not be afraid to say no to things, or remove themselves from projects or places that aren’t for them, even if they seem really enticing. You think you have to go through suffering because there will be an end result. I’ve dedicated my life to delayed gratification, so that kind of thing is really natural to me, I’m like, ‘I have to just grind through this,’ but sometimes it’s not for you.””

on being drawn to addiction medicine and academic detailing

I'm not sure what initially got me interested in addiction medicine, to be honest — maybe I was just interested in people's stories surrounding mental health and addiction in our culture. Seeing some transformations and success stories is so inspiring, to witness how somebody's trying to change their life and get back on their feet. I have a lot of respect for people struggling with addiction, not only dealing with their illness, but also navigating society. Soon after I started my clinical career, I learned of a new, emerging field that could make a difference for a lot of patients, not just the people I worked with in my clinic.

Academic detailing is an ever-evolving field that has to do with population health, so instead of working with someone one-on-one, you consider their condition from a bird's-eye view. You look at all these patients who are being treated and the different patterns of prescriptions they're receiving. We go through the current research, figure out what has good evidence supporting it, what doesn’t, and summarize that information for providers to apply. Tons of papers are published every day, and providers don't have the time to go through and figure out: What's evidence-based? What's not? How does this apply to my practice? Academic detailing does that, and we make little brochures of provider-friendly materials with nice graphics, two-page information sheets and things like that, in which we summarize all the pertinent information for them.

on the projects academic detailers develop

Fighting the opioid epidemic in the treatment of chronic pain is one of the big projects that academic detailers got involved in. We look at these opioid prescriptions, and we try to figure out what happened, did these patients get started on this drug within our healthcare system? What kind of pain are they being treated for? You can't treat all kinds of pain with opioids. We figure out different ways of addressing these issues and create projects around them. It’s up to us to talk to a provider who prescribes a lot of opioids, or teach them about other ways of treating pain, sometimes Eastern medicine or Reiki even, or we had a therapy group where patients would meet with a horse trainer, and hang out with horses. There’s strong evidence that it helps with chronic pain, just having a connection with these animals. It's not always medications — we try to work with individual providers and help them raise awareness about the problems with certain medications, and brainstorm how we can help their patients titrate down off their opioids. But that's just one example. PrEP, for HIV, is another medication I’ve worked a lot with in academic detailing — How to raise awareness of its uses, how to let people know that this medication is available.

““I got to the point where I was like, ‘I won’t have a home, the idea of “home” will never be something real to me, and maybe I can find strength in that.’ My whole identity was formed around this notion that I don’t have a home — I don’t belong somewhere, I don’t fit in, and that’s okay. And then I moved to New York, and I was like, I’m home. I’m gonna grow old and die here. I have community, and I can easily make friends, and I am happy. It’s just been amazing. I’m still figuring it out and processing it all.”

”

on finding ways to connect to iranian tradition

Growing up, my family always lived in places where there weren't a lot of Iranians, but being in that isolation led me to creating projects like Falgoush, an experimental publishing and curatorial project surrounding Iranian identity, because I was feeling very nostalgic and lost. I spent much of my time in the US as a young person trying to fit in and just get through my schooling. Once I graduated, I had all this time, and I didn't know what to do with myself. I didn't know who I was. It took me a while to be able to speak Farsi again, I had forgotten so much, I was just so busy for the better part of 25 years. Falgoush was born out of that, because I started watching Iranian films and reading about these esoteric traditions.

Falgoush is a ritual that I don't think people perform anymore, but during Chahārshanbe Suri, the last Wednesday of the year, people would wear a chador or a cloak or something to hide themselves, and they would eavesdrop. If the conversation they heard was positive, then it meant like their wish would come true or they would have a good year. If it was bad, it was the opposite. I don't know when people stopped doing this, maybe in the 50s or 60s — those are the last years I’ve seen this depicted in Iranian cinema. For some reason, the practice spoke to me. I love how it sounds: Falgoush, fal means divination, goush means ear.

Because I didn't have any background in Iranian arts and culture, I would run into these historical practices, thinking other people would know about them, but a lot of times they didn't. It’s important to me to rediscover these things for all of us in the Iranian community. I had been posting on Instagram, I didn't have anywhere else to save this research for myself, I had like 50 followers. Then a couple Iranian artists found it and it became what this project, Falgoush, has been ever since then.

Now that I've moved to New York, I think it's changed everything for me, because Falgoush was a personal project, really, for me to learn about my background, and our culture and our history. I was feeling super nostalgic, and it was feeding that craving. Now that I have this amazing community of Iranians here, I don't feel nostalgic as much. In fact, I already feel nostalgic for this moment, because I know it's so special, and I will look back on it as a really precious time. I’ve been curating and participating in more IRL community events, like the zine fairs to showcase works of Iranians and SWANA artists, and I'm just hoping that they will inspire people to document their stories and publish them, especially since books as a format have always been so censored in Iran.

““I feel like with pharmacists, we either get so heavily like obsessed with experimenting with cosmetics, or it’s like, ‘I don’t want to touch any chemical things.’ I feel like I’m becoming a member of the latter group. I’ve really slowed down with like skincare and things like that because I just don’t know the long-term effects.””

on what inspires her in every facet of her life

Seeing the humanity of my patients, and how sometimes people are able to transform their lives, and how hard some people have to work at the “easiest” things, cleaning their house, being able to take a walk, things that I take for granted. People still find a way to live, right? To find joy, even. The artists I work with are super inspiring to me, especially artists in Iran. I think being an artist is so hard, I have so much respect for the work that they all do. Living in Iran and doing that kind of work is just unbelievable, and they still pursue it because they have this fire. There's nothing more beautiful to me to see people pursuing that passion. In general, inspiration-wise, I love being Iranian. I always tell my friends that even if I weren't Iranian, I'd be that weird person who’d go to Iran as a tourist and spend months there. I just think that part of the world is so beautiful, and there's so much history there. In Iran, we don't really have a whole lot of independent institutions, so we're picking and choosing only certain parts of our history and arts and culture — I hope Falgoush will help dig in and discover beautiful things about all of our experiences that we should celebrate.

on what she’s reading

I discovered The Sense of Unity by Nader Ardalan and Laleh Bakhtiar through my research for a book I’m working on. It came out in the 70s and it's a very hippie take on Iranian art and architecture. These two authors looked at Sufism and how it informed Iranian architecture — it’s such a foundational text, and it talks about the different colors used in the buildings and what each of them means, and all the symbology and different patterns. I feel like everybody needs to know about this book, especially Iranians.

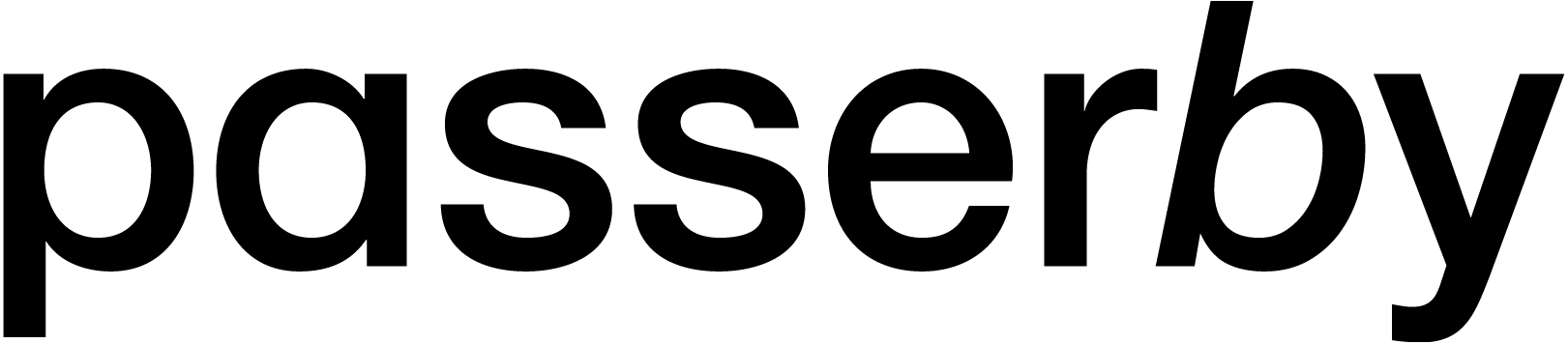

Other books I have on hand are: English Eccentrics by Edith Sitwell, Football by Jean Philippe Toussaint, High Tide of the Eyes by Bijan Elahi, Insurgent Aesthetics by Ronak K. Kapadia, Women With Mustaches and Men Without Beards by Afsaneh Najmabadi, After the Last Sky by Edward Said, Anadolu Psych by Daniel Spicer, John Waters: Indecent Exposure by Kristen Hileman, The Afkhami Collection of Modern and Contemporary Iranian Art by Sussan Babaie, Natasha Morris, and Venetia Porter, and two editions of The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan by James Morier.

on her beauty routine and personal style

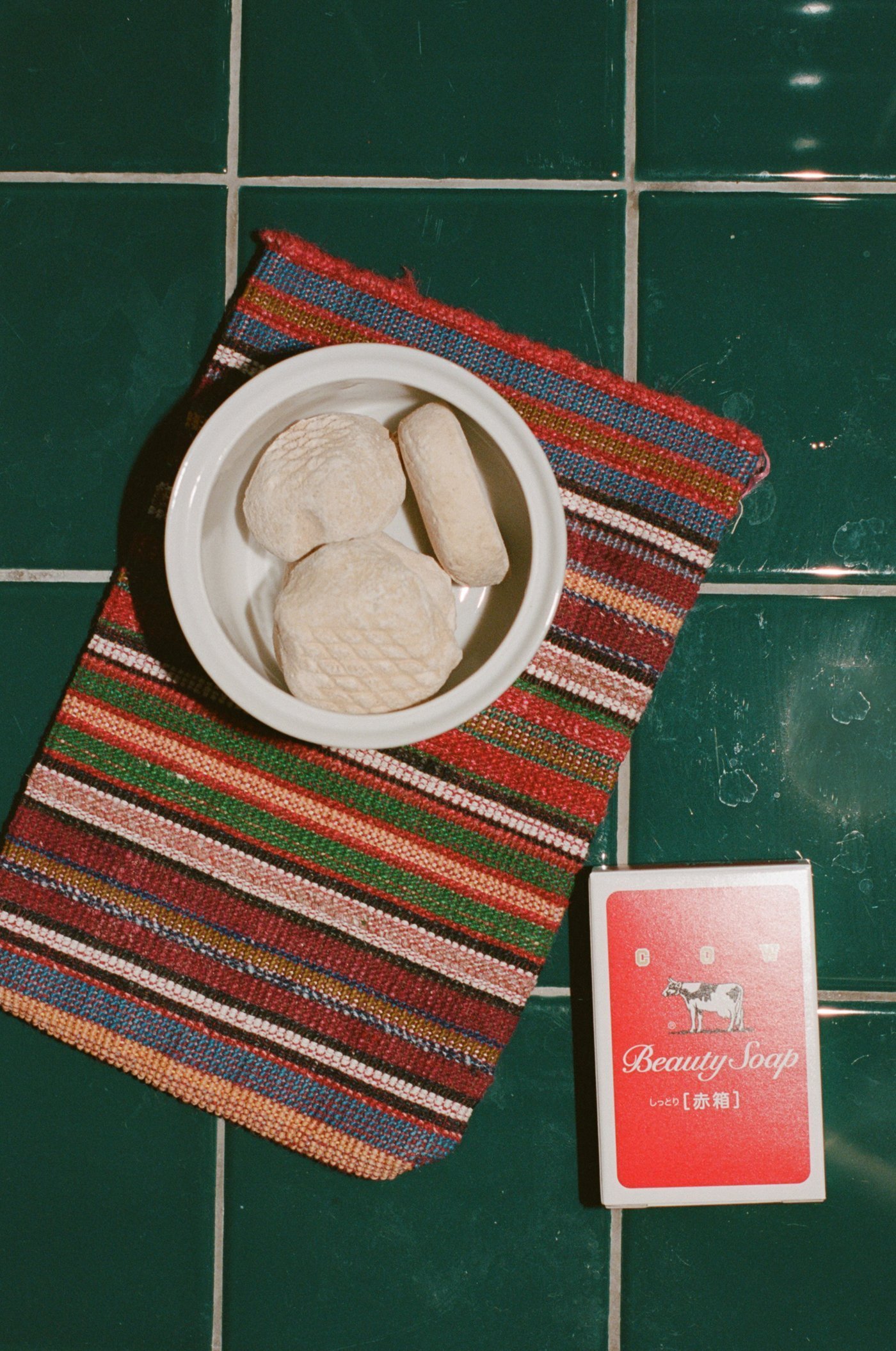

They are these little soaps called Sefidab, more like a soapy clay, made out of animal products, they're totally natural. Then you have a super abrasive glove, a Kesseh, and you get it wet, and with the clay stuff you exfoliate your skin but it's so effective that these dead skin slivers fall off of you like little worms. It's a really gross thing, but if you have a true partner, they won’t mind — That’s how you know they really love you, they might help get your back and stuff. When you do that, you come out of the shower feeling like you don't have your exterior layer of skin, like your body is breathing, you look really red for a while but it's just the best. The less aggressive version of the glove is a Japanese product from Sasawashi. I use that every day and that's really nice. That's all for skin, I just do maybe SPF, and I usually just wear a really silly hat to block the sun physically as much as I can. I don't really wear makeup that much, maybe I like the black liner because it's an Iranian thing. I use Tarte’s Sex Kitten eyeliner, I love the little sponge at the end to smudge it up. I also have in my makeup bag: Maybelline Great Lash, Burt’s Bees lip balm, Laura Mercier tinted moisturizer, Tower 28 bronzer, and Josie Maran powder. Classics.

My style is really inspired by the 60s and 70s in Iran, what the girls would wear back then. There was the psychedelic aesthetic, and I am very inspired by that part of the world, so it feels really authentic and fun. I try to buy vintage and secondhand as much as I can, just basic pieces I can wear for a very long time. But I also love to buy things from the creatives in our community. There are a lot of people who come up with different t-shirts — LEBĀS has really cute stuff. I got to meet her now that I live in NYC. I also love Znali’s clothing because it's unisex and has really fun patterns — it’s very inspired by people in their family.

zari’s favorite spots in nyc

One of my favorite places to spend time in is the main branch of the New York Public Library on Park Ave — I highly recommend Room 300 if you're into art and architecture, they have some really historic stuff — I got to hold a book that was like a hundred years old and I was like, do I need to wear gloves to handle this? Little Roy cafe is really cute and nostalgic when I take my dog out on a walk. I actually like Prospect Park more than Central Park, just because Brooklyn's so fun to people watch in.

interview and images by clémence polès, edited by em seely-katz